There’s no doubt about it: 2014 was certainly a life-changing year for me. My twin daughters, Scarlett and Madison, made their grand entrance in July and they finished out the year able to coo, squawk (for lack of a better term), swing toys and smile with a sincerity that is bewilderingly beautiful.

But you’re here for the photographs, right? Well, my work throughout 2014 was more diverse than ever. I delved deeper into Connecticut’s natural landscapes; still seeking out little-known places, but also making a more concerted effort to find fresh ways of interpreting more prominent natural landmarks. I also made my way out west to New York’s Catskills where I had the privilege of shooting some truly sublime waterfalls.

And undoubtedly one of the most striking shifts in my work during 2014 has been my fascination with farmlands. From sprawling cornfields and time-worn barns to grazing livestock and clusters of round hay bales, I’ve found great satisfaction in broadening my subject matter beyond purely natural landscapes. The reason for this change is simple: after years of landscape photography, I’ve finally discovered that what motivates me —what keeps me forever in search of the next vista— is the gratifying quest to express the essence of New England’s heritage. Not just our natural heritage, but also our cultural heritage: our farms, our old mills, our lighthouses, our covered bridges and our untold miles of fieldstone walls.

So without further ado, here are my favorite thirty photographs from 2014.

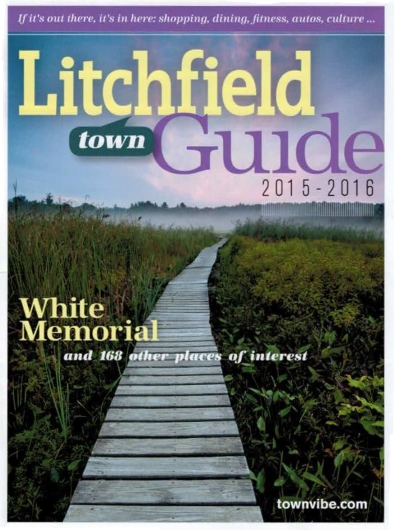

Heavenly Bantam

Little Pond, White Memorial Conservation Center, Litchfield, Connecticut

Even though the weather report called for partly cloudy conditions on this humid morning, there was mostly just vacuous, open expanses of sky over these lush wetlands in Connecticut’s Northwest Hills. It wasn’t until I was on the boardwalk heading back to the trailhead that I paused momentarily to take a look at some of the large cattail leaves nearby. Glancing beyond the leaves, I noticed an opportunity to capture the searing glow of the morning sun through a lingering mist which still swirled about landscape.

Yankee Farmlands № 9

East Granby, Connecticut

This time-worn barn along a rural stretch of road in East Granby had caught my eye weeks before I produced this image. I drove by it on several different occasions as we transitioned into October, waiting for just the right conditions which would conjure the nostalgic feel of a New England autumn. While the barn may be what folks tend to notice first, its stately, half-bare companion tree is really just as much the subject of this image.

Legend of Bash Bish

Bash Bish Falls State Park, Mount Washington, Massachusetts

Throughout 2014 I finally began to sincerely delve into the realm of black & white photography. The famous Bash Bish Falls of Massachusetts’ Berkshires was among the first subjects that I tackled and my interest with this image nudged me to keep at it the rest of the year, even if only infrequently.

Bee Brook Autumn

Hidden Valley Preserve, Washington, Connecticut

By early October, most of Connecticut was still a few weeks from reaching peak autumn color, but the forests of Washington were already ablaze when I visited Bee Brook on a cool, overcast morning. Under spring or summertime conditions, this perspective is somewhat unremarkable, yet it takes on an entirely different character when every square foot of the forest floor is jacketed with a vivid mosaic of fallen leaves.

Yankee Farmlands № 4

Bethlehem, Connecticut

When I happened upon this horse pasture just minutes after dawn, I knew I had quite a find on my hands. Horses stood quietly upon the hills, seeming almost contemplative amidst the hazy, humid atmosphere. Rendering a sunstar upon the back of the nearest horse was tricky, but I think it worked to introduce a stronger, more dramatic focal point in the composition.

Awosting from the Heavens

Awosting Falls, Minnewaska State Park, Ulster County, New York

Several of the waterfalls in New York’s Catskills and Shawangunks feature impressive freefalls into broad, amphitheater-like gorges and Awosting Falls is no exception. For this shot, I used very deliberate framing and the perspective distortion of an ultra-wide-angle lens to create the illusion that the waterfall was dropping clean out of the sky into a dark pool amidst angular boulders and woodlands. In reality, it was plunging into the gorge from a ledge about 60 feet above my head.

Black Rock Crescendo

Black Rock Harbor Light, Seaside Park, Bridgeport, Connecticut

The Black Rock Lighthouse is a welcome anachronism that sits upon a small island just off the coast of Bridgeport, one of Connecticut’s largest and busiest cities. When you walk to the island via a 1,000-foot breakwater and stand beside the tower as the sun rises over Long Island Sound, it’s surprisingly easy to forget about the warehouses and smokestacks which crowd the shores of the nearby mainland. I shot this photograph on the last day of winter in 2014 and the sunrise was so astonishingly beautiful —and yielded so many striking images— that I had quite a bit of difficulty selecting a “favorite”.

As Yet Untitled

Broad Brook Reservoir, Cheshire, Connecticut

I spent the later half of my childhood just minutes from Broad Brook Reservoir, so its wooded shores and placid waters are inextricably linked to my memories from those early days. There’s just something about this lake which I find deeply comforting, so I felt especially privileged to be there during a positively glorious autumn morning in October just as strong, sharply-angled sunlight illuminated the lakeside forest.

Bull’s Crossing at Kent

Bull’s Bridge, Kent, Connecticut

For a good deal of 2013, I had been working on my Old Timbered Crossings project in which I sought to capture the distinctive character of each of the three 19th-century covered bridges remaining in Connecticut. Despite a handful of visits to this iconic bridge spanning the Housatonic River in Kent, it was the only one of the lot that I hadn’t checked off the list before the end of that year. When I lamented to a friend that none of my previous shots quite fulfilled my vision, he suggested trying to shoot the bridge from the opposite side. That simple recommendation held the key I’d been searching for and I managed to produce this photograph just about a week later on a frigid morning in late January 2014.

Carpenter’s Summer

Carpenter’s Falls, McLean Game Refuge, Granby, Connecticut

Carpenter’s Falls, a small waterfall in the expansive McLean Game Refuge, was somewhat starved for water when I arrived in late June. I was half expecting this, since waterfalls that are raging with spring rains and snow melt generally tend to grow more and more tame as the months progress, bringing hotter temperatures and reduced rainfall. Sometimes this reduced water volume can sap a waterfall of its aesthetic impact, but Carpenter’s Falls managed to retain its lively character even as a singular braid of wispy whitewater amidst moss and woodland grasses.

As Yet Untitled

Chapman Falls, Devil’s Hopyard State Park, East Haddam, Connecticut

Chapman Falls is one of Connecticut’s more prominent waterfalls. It is the aesthetic centerpiece of Devil’s Hopyard State Park and probably draws more visitors than any of the 1,000 acres of forest that surround it. As such, it tends to be photographed very often and it’s difficult to create a photograph there which makes an original statement. So, rather than shooting a head-on “portrait” of Chapman Falls, I instead mounted my camera on the tripod just inches from the water and let the swirling foam at the base of the falls do most of the talking.

Autumn at the Stone Church

Dover Stone Church, Dover, New York

The Dover Stone Church is one of those natural landmarks that was once quite celebrated during the Victorian Era, but which more or less fell off the map as long-distance automobile travel began to extinguish the novel excitement behind so many local curiosities in the American Northeast. Although it looks to be a deep cavern plunging into the earth, the Stone Church is actually more akin to a small slot canyon. Over thousands of years, the brook I’ve portrayed in the foreground managed to eroded its way down through a massive rock outcropping, eventually chiseling out an impressive, 30-foot-tall hollow in solid stone.

Yankee Farmlands № 12

Avon, Connecticut

The first snowfall of winter this year blanketed the stubble of harvested cornstalks at this farm on the borderlands between Avon and Farmington. This freshly-frosted landscape was positively beautiful, but it was the particularly the bare, sprawling crown of this lone tree amidst the fields that really caught my eye. Composing the shot such that the sun blazed through the silhouetted branches was my way of drawing the viewer’s eyes into the heart of the scene.

Yankee Farmlands № 16

Durham, Connecticut

The transitional period between autumn and winter is, for me at least, the most challenging time of year to pursue landscape photography in New England. It’s late enough that the trees have grown bare and colorless, yet oftentimes still too early for a persistent snowpack. The result is a decidedly bleak landscape which sometimes leaves me feeling a bit uninspired. Nonetheless, I still hit the road and roll the proverbial dice in search of rare opportunities. My efforts paid off this time around when I discovered a gated pasture overlooking a wooded hill painted liberally with the warm light of dawn.

As Yet Untitled

Bridgewater, Connecticut

Lover’s Leap State Park in Bridgewater offers a spectacular cliffside overlook with panoramic views of Lake Lillinonah, a scenic reservoir on the Housatonic River. I was sure that a blanket of fog rolling over the landscape would make for an epic sunrise photograph from the overlook on this particular morning. Instead, it thickened to the point that I couldn’t see anything more than 100 feet away, much less the sprawling lake below. Thankfully, my favorite image of the day was taken in the dark twilight before I had even made my way to the overlook! The fog was still relatively thin this early in the morning, offering the opportunity to capture a positively ethereal image of this antique iron bridge spanning the shadowy gorge of the Housatonic just upstream of the reservoir.

Kaaterskill Shadows

Kaaterskill Falls, Kaaterskill Wild Forest, Hunter, New York

I had done several hours of online research and looked at dozens of images before setting out into New York’s Catskills to photograph Kaaterskill Falls, but seeing this majestic waterfall in-person still proved to be a genuinely memorable experience. Certainly one of the grandest waterfalls in the American Northeast, Kaaterskill Falls plunges some 260 feet over two impressive drops through a cavernous gorge crowded by woodlands. This black & white photograph was certainly among my favorites from that trip, featuring the upper tier of Kaaterskill as it freefalls 170 feet over a precipitous cliff into a shallow pool below.

Last Throes of Winter

Kent Falls State Park, Kent, Connecticut

Kent Falls is one of those places that has, as I oftentimes put it, generally been “shot to death” by Connecticut nature photographers. What I mean is simply that the obvious, scenic viewpoints along the falls have been photographed so many times that it’s extremely challenging to go there and produce images that offer some measure of uniqueness. I had that very thought in mind on a frigid morning in April after a springtime squall dumped a few inches of snow on Connecticut’s Northwest Hills. Instead of shooting for the larger waterfalls, I decided emphasize the more subtle characteristics of the cascades, the striated bedrock of the riverbed and the freshly-frosted forest.

Winter’s Kiss

Black Pond SWMA, Middlefield, Connecticut

Between the subtle lighting and the delicate frost, this jumble of fallen oak leaves offers me more than just a visual impression… I can feel the chill in the air and hear the brittle, icy leaf litter crunching underfoot as I walk along. When I arrived at Black Pond on this cold morning just about a week before the winter solstice, I had every intention of leaving with a landscape photograph. Suitable conditions just didn’t materialize, but that proved to be a stroke of luck, since I might otherwise have carelessly stepped right over this miniature leafscape.

True Niagara

Niagara Falls, Canada

When I initially attempted to photograph Niagara Falls from the west corner of the Canadian horseshoe in early April, I was confronted by an absolutely frigid mist blasting so forcefully out of the gorge that I could scarcely finish a single exposure before my lens was glistening with water and required cleaning. Shooting conditions like that simply weren’t going to work, so I was faced with trying to find an alternative. As it happens, I did ultimately figure out how to shoot these falls without soaking my camera and this photograph, in which I tightly framed the falls, mist and upstream rapids, proved to be my favorite image of the trip. How did I do it? Well, I shot it through a window more than 30 stories in the air during morning twilight… all from the warmth and privacy of my hotel room. Sometimes, it’s best to improvise!

Dominion of the Gulls

Pleasure Beach, Bridgeport, Connecticut

Anyone not well-versed in the fairly obscure story of Pleasure Beach may wonder how so many seashells could find their way on top of a bridge. Interestingly, they were all deposited there by seagulls which cleverly break open snails and clams by dropping them upon the rigid bridge decking from a few dozen feet in the air. Because Pleasure Beach has been abandoned for nearly two decades, there was more than enough time for the fragmented shells to accumulate. (Side note: After several years of abandonment, Pleasure Beach was officially reopened as a city park in 2014, just a month or so after I took this photograph.)

As Yet Untitled

Sleeping Giant State Park, Hamden, Connecticut

One thing is for sure: man-made structures were more prominent in my photography throughout 2014 than they had been for all of the prior years combined. My Old Timbered Crossings project, for example, featured covered bridges and my on-going Yankee Farmlands project oftentimes incorporates barns, silos and fences. In this case, my subject was the ruins of a long-abandoned quarry facility in Sleeping Giant State Park. The old quarry operation blasted traprock from one of the adjacent Sleeping Giant mountains until 1933 when determined conservationists thankfully purchased and preserved the land.

Saugatuck Whitewater

Saugatuck Falls Natural Area, Redding, Connecticut

By mid to late summer, the Saugatuck River in Redding assumes a fairly tame demeanor as it loses water volume to dwindling rains and hotter temperatures. Head there in May like I did, though, and you’re likely to find the banks inundated and the waters angrily peeling through boulder-laden rapids just below Saugatuck Falls. The powerful impression of rugged remoteness contained in this photograph is one reason why it’s among my favorites of 2014. Looks can be a bit deceiving, though: if I were to walk just 200 feet west from this scene through woods, I would find myself on the shoulder of Route 53.

As Yet Untitled

Scovill Reservoir, Wolcott, Connecticut

Scovill Reservoir is near and dear to me… and when I say it’s near, I mean that I can drive there in a few seconds. Not only is it my bass fishing hole, but it’s also a fairly picturesque lake in its own right. The advantage to living right beside this wooded pond is that I constantly have the opportunity to make the most of interesting conditions, experimenting with new perspectives or re-interpreting the view from my favorite spots. This photograph of a small cove is my top pick for Scovill Reservoir in 2014 because I was able to bring together so many elements: the dramatic clouds of dawn, the densely wooded shores, the lush vegetation thriving at the water’s edge and fallen pine needles collecting in the shallows.

Yankee Farmlands № 7

East Windsor, Connecticut

This past summer, I began working on my Tobacco Valley project in which I seek to document the rhythms, sights, and textures of tobacco agriculture in the Connecticut River Valley. I’m very excited about this project, but I’ve mostly kept my work on it under wraps until I can complete a year’s worth of shooting and really capture the character of these unique Connecticut farmlands throughout every season. I’ll make an exception for this retrospective, though: this photograph of a shade tobacco farm in East Windsor was certainly among my favorites for 2014 (you can see one more piece from my Tobacco Valley project in this retrospective, also; I just couldn’t help myself!). If you’re interested in seeing the full range of work included in my Tobacco Valley project, rest assured that I’m still out there actively shooting. Keep your eyes peeled in the later half of 2015!

Shepaug Rejoicing

Washington, Connecticut

When I captured this photograph of a glorious shaft of light pouring over the forest into the Shepaug River gorge in Washington, I couldn’t possibly have known that my camera would vanish without a trace just a week later. Indeed, one of the low points of 2014 was undoubtedly waking up in early autumn to find that almost all of my gear had been stolen from my truck… right in my own driveway no less! That was a pretty demoralizing blow which came in the middle of one of New England’s most photogenic times of year. Insurance came through, of course, and I was back up and running by early November… but by that time, the forests were more or less stripped bare.

Yankee Farmlands № 5

Simsbury, Connecticut

This is probably one of the more subtle photographs that made it into my Favorite 30 of 2014. Driving along on a quiet road in Simsbury, I discovered this cluster of large, round hay bales nestled beside a small stand of woodlands just days after they’d been collected from an adjacent hayfield. There’s no eye-melting sunrise here, no majestic waterfall, no dreamy fog; just the quietude at the edge of the farm and a beautiful interplay between light and shadow that just sort of grasps my sensibilities for one reason or another.

As Yet Untitled

Talcott Mountain State Park, Simsbury, Connecticut

Rising nearly 1,000 feet over the surrounding landscape in Simsbury, Talcott Mountain is certainly one of the more prominent traprock ridges of the Metacomet Range. Perched atop the high cliffs is the 165-foot tall Hublein Tower, imparting a unique element to the profile of this otherwise gently-sloping, wooded ridge. I’ve photographed Talcott Mountain several times during every season, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen it looking quite as beautiful as it did on this day in early October as the setting sun cast a warm glow upon the landscape and threw long shadows across the cornfields. I hadn’t even intended on stopping when I drove by, but within moments of passing this vista I knew I had to turn around and get the tripod set up as quickly as possible.

As Yet Untitled

Simsbury, Connecticut

In the 1920s and 1930s, roughly 15,000 acres of farmland in Northern Connecticut was dedicated to the cultivation of tobacco. Although some of the world’s finest tobacco still comes from that region, the market has atrophied in the past century and most of the old farms have been supplanted by corporate office buildings, suburbs and woodlands. Drive around enough on the backroads, though, and you’ll occasionally stumble upon decades-old abandoned barns that were once used to dry the freshly-harvested crops. I captured this image inside one of those old barns as bright, mid-day sunlight pierced the weathered siding.

The Wild Coginchaug

Simsbury, Connecticut

If you found me out on the Coginchaug River on this drizzly, overcast day in late April, chances are pretty good that I would’ve been donning my waders, fishing vest and trout rod; fishing was really all I had in mind at the time. After hooking into a few, I set my attention to Wadsworth Falls and noticed that the roaring whitewater was churning up patches of foam that drifted quite far downstream before dissipating. I suddenly envisioned an image and returned to my truck, swapping my fishing pole for my camera gear. This was the photograph which was born out of that chance visualization.

As Yet Untitled

Westbrook, Connecticut

Taken in the context of Connecticut’s 100 miles of coastline, West Beach is just a little-known, 1/2-mile sandy beach in the small, little-known town of Westbrook. I suppose that the ordinary person might consider it to be a fairly unremarkable stretch of shoreline. And yet, having grown up there each summer as a child, I cannot possibly overstate the immense role that this beloved beach has played in my life. Years of exploring the sandbars, offshore islands and saltwater wildlife has indelibly etched this seascape into my psyche… perhaps even helped to shape me into the person I am today. I take several dozen photographs of West Beach every year and this past year was no exception, though this piece was easily my favorite of 2014.

Looking Ahead to a Promising 2015

There you have it… my favorite 30 photographs of 2014. Again, many strong photographs just couldn’t be fit edgewise into this limited-length line-up, so be sure to check out the broad range of work that I released over 2014 at my online galleries. Also, be sure to follow my work on the social network of your choice: Facebook, Flickr, Google Plus, Instagram… I’ve got em all.

But most importantly, I hope you look forward to a promising 2015 and embrace the opportunities and fortunes that come your way, while weathering with resolve the difficulties that may lie between. I leave you now with the words of Henry Ward Beecher:

“Every man should be born again on the first day of January. Start with a fresh page. Take up one hole more in the buckle if necessary, or let down one, according to circumstances; but on the first of January let every man gird himself once more, with his face to the front, and take no interest in the things that were and are past.”

-Henry Ward Beecher (1887)